This paper explores the relation of money, market exchange, and reciprocity, specifically by investigating how businesses use local currencies. Local currency (Transition currency, Regiogeld) is a particular form of alternative monies that circulates in parallel to and backed by legal tender within a restricted local space. It is argued that, notwithstanding the economic objectives of such schemes and their proximity to the formal economy, local currencies can be understood as means of payments for particular, convivial purposes that are based on reciprocity and commensality. The analysis is based on Karl Polanyi’s distinction between all-purpose and special purpose money and his identification of different modes of exchange. Viviana Zelizer’s notion of earmarking is then applied to local currency schemes in order to assess how and for what purposes businesses and traders that accept local currencies actually use it.

This paper originally appeared in Behemoth vol 9, no 2, 2016, pp. 22-36. It is part of a special issue (edited by Axel Paul) on “Money’s Future and Future Monies” (https://ojs.ub.uni-freiburg.de/behemoth/issue/view/77).

Philipp Degens, Department of Socioeconomics, University of Hamburg. philipp.degens@uni-hamburg.de.

Money is (still) usually regarded as unidimensional and homogeneous. It comes with rationality and calculation. Because of these features Georg Simmel calls it “colourless” and “characterless” (Simmel 1989, 497). Moreover, money is closely related to markets since it tremendously reduces transaction costs and allows for economic exchange that primarily relies on prices. According to this classical view, money is an expression of instrumentally rational (zweckrationale) relations between individuals. Due to its very nature, it de-personalises and reifies social relations (Mikl-Horke 2011, 190). However, this conception of money has been challenged by approaches that take into account the various social meanings, the cultural practices, and the particular social relations by which money itself is constituted (e.g. Zelizer 2011).

Against this background, this paper deals with the relation between money and markets by exploring usages of local currencies by small businesses and traders. Local currency as it is understood in this context refers to a particular form (that is backed by and convertible into legal tender) of complementary currency. It can be regarded as an agreement among a particular group in a local space to use a medium of exchange that is different from but pegged to legal tender (Hallsmith/Lietaer 2011, 51). Within the last two decades, various forms of complementary currencies emerged all over the world, aiming at “taking back local economies” (North 2014). In strict economic terms, they are, however, still neglectable ; turnover and money supply is rather low. Yet, in response to the growth of the movement, even central banks start to address complementary currencies, mainly by asking whether or not such schemes pose a threat to the money system (see, for example, Naqvi/ Southgare 2013).

I intend to show that money in this form is not always an instrument to mediate pure market relations. I do so by exploring a form of local currency that circulates alongside legal tender in a restricted local space. Among the objectives of local currency schemes is the stimulation of the local economy by boosting local and independent businesses and increasing demand for local goods and services. The idea, in other words, is to offer a particular monetary form for a local market place. But, nonetheless, it cannot be regarded as a pure market instrument.

In order to assess the relation between local currencies and the market, I introduce two approaches to the multiplicity of monies. These are offered by Karl Polanyi and Viviana Zelizer. Both show that money is not always homogeneous, perfectly fungible and universal (on differences and the compatibility of these approaches, see Steiner 2009). Polanyi also synthesises different institutional patterns of trade, showing that exchange is not necessarily restricted to market exchange but can be guided by reciprocity or redistribution.

My aim is to show that the usage of local currencies among businesses does not reflect market-based social relations, but relations that are based on reciprocity. Local currencies, even if designed as a tool for the stimulation of local marketplaces, serve to a certain extent as a means of payment for special purposes within reciprocal relations. In this sense, it partly reverses tendencies of reification and de-personalisation that are commonly ascribed to money. The analysis deals with practices of monetary uses and their underlying meanings. I focus on small businesses and traders who accept local currency (and not on private consumers – see Thiel 2011, 2012 for such an analysis) because these actors apparently belong to the conventional economic sphere ; they act within the realm of the formal economy and within markets. Selected results from field research [1] on the Brixton Pound in London, the Stroud Pound in Stroud, UK, and on the Vorarlbergstaler in Vorarlberg, Austria is presented to show how local currencies are used for community purposes. These cases all represent a particular type of local currency ; “Transition currencies” (Ryan-Collins 2011) or “Regiogeld” (Degens 2013, 24ff.). A distinguishing feature (compared to other complementary currencies) is that they are backed by and pegged to legal tender in order to attract high numbers of businesses and to achieve high turnover. However, I aim to show that this closeness to legal tender does not mean that these currencies function in the same way as common money.

The paper is organised as follows : First, I assess the two different notions of multiple monies offered by Karl Polanyi and Viviana Zelizer. I argue that Karl Polanyi’s distinctions between a) all-purpose and special-purpose money and b) market exchange, reciprocity and redistribution as different modes of exchange coincide with regard to complementary currencies. Then, I turn to Zelizer’s rejection of the notion of a homogeneous and perfectly fungible all-purpose money and her emphasis on particular practices within social relations that form the meaning and restrict the fungibility of money. Applying these considerations to the field of local currency, I first discuss Blanc’s (2011) typological approach to various forms of community currencies issued and controlled by civil society actors. Blanc employs Polanyi’s distinction between market exchange, reciprocity and redistribution and marks the type of CC discussed here as “economic projects” that are based on “market exchange”. My field research shows that Blanc’s classification of local currencies as “economic projects” fails to reflect the way that businesses actually make use of local currencies and the meanings they ascribe to it.

In this first part of the paper, I introduce different approaches that deal with the multiplicity of monies, and with different modes of trade. This discussion of classical accounts of the internal variety of money offers a conceptual background against which alternative currencies can be characterised.

2.1. Polanyi on special-purpose money and different modes of exchange

In a seminal paper on monetary objects and monetary uses, Karl Polanyi argues that any object can function as money, and that monetary functions are institutionalised separately and, also, independently from each other. Polanyi brings forward various historical examples of forms of money that do not comprise the canonical functions as means of payment, unit of account, store of value and medium of exchange (Polanyi 1968). In the context of unfolding “[t]he semantics of money-uses”, Polanyi claims that money is usually understood in overly narrow terms, because it is conceived only in the form it takes within the “market organization of economic life” (Polanyi 1968, 175). In order to deepen and widen the understanding of money and its functions, Polanyi refers to historical examples of various monetary objects and forms. He derives his concept of “primitive money” (Polanyi 1957, 191) from its uses as payment, standard, hoarding, and exchange. For Polanyi, only modern money combines all these functions (unit of account, medium of exchange, means of payment, store of value) at once, in one (national) currency. By contrast, pre-modern monies usually do not combine these functions but institutionalise them separately. This, in some sense, leads to a multiplicity of monies, because some objects may be used in payments for the trade of goods, some in religious purposes, others in marital affairs etc.

Polanyi thus establishes a sharp distinction between pre-modern and modern money. For him, modern money is aimed to come close to the perfectly fungible, homogeneous idea of money that can be found in economic textbooks. [2] Applying the underlying distinction, complementary currencies can be regarded as special-purpose monies as they do not aim to fulfil all functions of all-purpose money at the same time (Seyfang/Longhurst 2013, 67).

Polanyi offers a second distinction that can fruitfully be employed to the analysis of complementary currencies as it allows to elaborate on the particular special purposes of such monies (Blanc 2011). He identifies different forms of economic integration that are based on the distribution of resources in society : market exchange, reciprocity, and redistribution (Polanyi 1957).

If governed by markets, exchange takes place according to prices determined by the laws of demand and supply. Its prototype is on the spot exchange based on a free contract between individuals that bear no relations with each other. For Polanyi, market exchange is the predominant mode in modern societies. Yet market exchange is only one form of trade. Redistribution is the hierarchical counterpart of reciprocity as non-market mode of integration : it refers to the movement of goods or services towards an administrative centre, where they are collected. They might be consumed there or re-divided among the members of the group/political entity. Reciprocity refers to direct exchange of goods and services between people within non-market and non-hierarchical relationships. It is a symmetric form of non-market exchange. Reciprocity is often identified with the gift exchange as described by Marcel Mauss in his famous essay on the Gift (1990). Such a gift is not to be confused with an altruistic present ; it comprises both a voluntary and an obligatory character at the same time. A gift might “be motivated by generosity or calculation, or both” (Osteen 2002, 14). Mauss identifies an obligation to give, to receive, and to return a gift that is at the core of the irreducible simultaneity of freedom and obligation.

Notwithstanding the ambiguities of terms like reciprocity or gift exchange, they offer important insights for the analysis of money. It is misleading to solely emphasise the connection of money with markets. Instead, money can in principle also be linked to other modes of trade/exchange, like redistribution and reciprocity. [3]

2.2 Zelizer on special monies

In a sense, Viviana Zelizer’s (1994 ; 2011) approach supplements Polanyi’s concept of special-purpose money. She agrees that an analysis of money should start with its uses and the particular meaning that is attributed to it by its users. However, unlike Polanyi, Zelizer is concerned with modern all-purpose money, and with the factual limitations of this conceptual idea. Her main argument is that money is not as fungible and homogeneous as conventional theory suggests. Even modern, all-purpose money is restricted by its users and differentiated into special monies. Zelizer relates monetary practices to social relations and argues that people use techniques to differentiate monies in accordance with the particular relation that exists between them (Zelizer 2011, 390). She aims to show how money is socially and culturally shaped by its users via practices of earmarking. People do not regard every dollar as the same, but sort it, for example, according to source of income, spending purpose, or type of social relation money is used for.

Zelizer’s core argument proposes that the homogenisation and differentiation of money are intertwined i.e. two faces of one and the same coin. In order to understand Zelizer’s claim, two forms of the homogenisation of money have to be distinguished, money being the object in the first form, and the subject in the second : The homogenisation of money itself, and the homogenising effects of money on culture and social life (Dodd 2014, 287). The first dimension relates to the assumption of the exclusive homogenisation of money through the emergence of national currencies under the control of central banks, or, in the case of the Euro, even supranational universal money. This is the process of a change that money itself undergoes. The second dimension puts an emphasis on the homogenizing effects money has on other objects, particularly on social life. Simmel, for instance, describes money as a destroyer of shape (Formzerstörer, Simmel 1989, 360) and as a levelling force (Nivellierer, Simmel 1995, 121f). The homogenisation of money thus in turn leads to reification and rationalisation, creates calculative behaviour and undermines personal relationships.

Zelizer denies both assumptions of a homogenisation of money. She argues that the national control of money through a central bank does not necessarily lead to a simple homogenisation, but was and still is accompanied by tendencies towards differentiation. Cultural and social factors, which shape money from within, come along with this differentiation of money. Thus, while some social institutions may make money more uniform and more fungible, other – arguably more local institutions may counter this process, by implicitly or explicitly imposing restrictions on the use of this money. Furthermore, the assertion that money has a one-sided and context-independent influence on society cannot be maintained once these social and cultural imprints are acknowledged. Hence, Zelizer sees a dual dimension of money because on the one hand it is differentiated on a micro level but from a macro perspective it appears homogenous :

“All moneys are actually dual ; they serve both general and local circuits. Indeed, this duality applies to all economic transactions. Seen from the top, economic transactions connect with broad national symbolic meanings and institutions. Seen from the bottom, however, economic transactions are highly differentiated, personalized, and local, meaningful to particular relations. No contradiction therefore exists between uniformity and diversity : They are simply two different aspects of the same transaction.“(Zelizer 2011, 392)

Differentiation takes place via practices of earmarking. Zelizer names several techniques and subsumes, inter alia, both the establishment of social practices by which identical media are separated into distinct categories, as well as the “creation of segmented media” under the term earmarking. Zelizer explicitly regards the creation of local currencies as a form of earmarking (2011, 389). In the first sense, “earmarking” refers to social practices that modify money ; in the second sense, “earmarking” refers to the production or creation of new forms of money (Dodd 2014, 291f.). The broadness of this term might be considered a bit slippery. [4] [4] However, for the purpose of this paper, it is sufficient to acknowledge that money might be differentiated both in its use and in its creation. Local currencies thus might be regarded as the result of earmarking processes, yet – like all forms of money – they might even be further restricted, earmarked, and shaped by its users. To illustrate this point, I turn to one particular type of complementary currencies which is called Regiogeld or Transition currency.

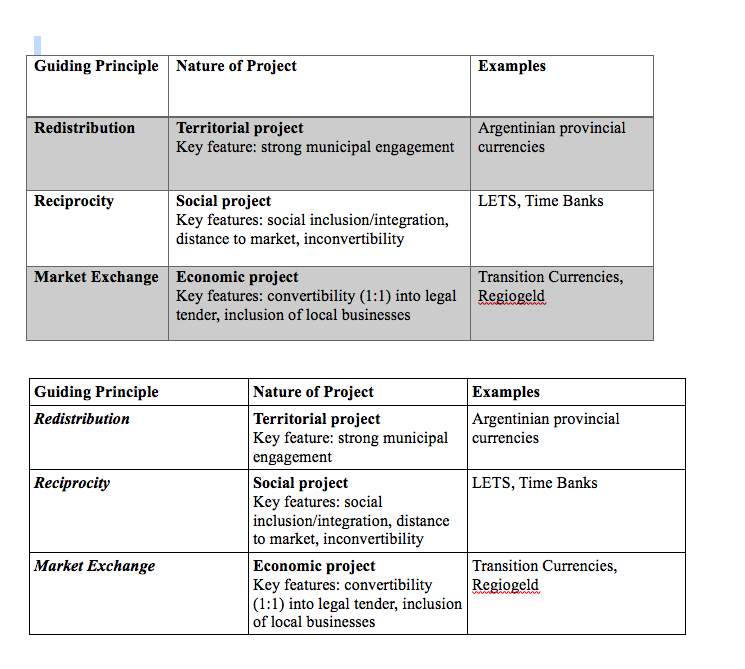

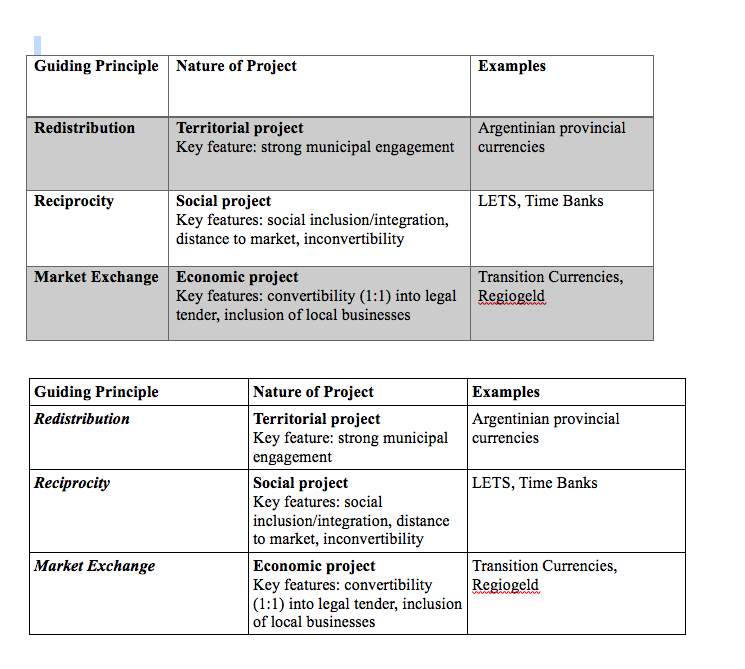

Based upon Polanyi’s distinction between market exchange, reciprocity and redistribution, Blanc (2011) offers a typology of civil society based complementary currencies (CCs). Blanc first classifies CCs according to their respective special purposes. He directly relates different types of complementary currencies to these three modes of exchange identified by Polanyi mentioned above (reciprocity, market exchange and redistribution). For Blanc, these three different forms of institutionalised social-economic relations can be redefined and rephrased as ‘market’, ‘state’, and ‘community’ (Blanc 2011, 6). Each implies distinct guiding principles and requests a certain set of behaviours that are structured by particular norms and values. By applying these modes to complementary currencies, Blanc refers to them as economic, territorial, and social projects (see table). There is no need to describe his approach in depth here. Yet in order to assess particularities of local currencies as “economic projects”, I mark down differences with respect to social and territorial projects. Note that I – deviating from Blanc’s terminology – use the term “local currency” for a particular kind of economic projects simply because those schemes refer to themselves as a local currency or Regiogeld (regional money).

Types of CCs based on redistribution, reciprocity, and market exchange (based on Blanc 2011, 7).

Blanc labels a first type “territorial projects” because their purpose is to define and protect the economic affairs of a politically defined territory. Municipalities (i.e. low-level state actors) implement such CCs in order to pursue these ends. The guiding principle, according to Blanc, is redistribution or political control. The provincial currencies in Argentina which circulated from 1984 to 2003 are given as an example.

A second type is based on reciprocity. Local exchange trading systems (LETS) and time banks belong to this type which Blanc labels as “social projects”. They primarily aim at integrating marginalised people and contain a certain distance to the market and the formal economy. Generally, such CCs are not convertible into legal tender although they might be pegged in the sense that legal tender serves as a unit of account. Others are based on time, meaning that the amount of labour time necessary to produce a particular good determines its value within the scheme. Mixed payments (e.g. LETS tokens and legal tender), however, might be possible. Many of such schemes have been successful for a rather short period of time, yet very few turned out to be viable in the long run, usually on a very low level. Yet despite their limited economic impact and the experience of failures, such schemes seem to be still attractive to many of its members (Peacock 2014).

A third type of CCs comprises local currencies such as UK Transition currencies, German Regiogelder, HOURS schemes, and community development banks in Brazil (like the Banco Palmas). According to Blanc and others, these recent schemes are best perceived as “economic projects” that build upon the guiding principle of market exchange. These schemes rely on the inclusion of businesses ; therefore they entail a proximity to market and formal economy. The general idea is to attract small and medium enterprises in order to increase the impact (compared to LETS or Time Banks) and to set free a higher potential to grow. In part, their design is a response to the limited capabilities of Time Banks and LETS to generate economic impact (North 2014, 251f.). Their objects are stated as a) to increase local economic activity, and b) to support local businesses (Michel/Hudon 2015, 162). This type seeks a greater economic impact by including local producers and retailers (Blanc/Fare 2013, 68).

In order to better understand the particular feature of specific monies that I am interested in, it is necessary to take a closer look at particular local currencies. The Brixton Pound, the Stroud Pound, and the Vorarlbergstaler can all be classified as Blanc’s third type. This third type of CCs, local currency, is usually fully backed by legal tender, it is convertible and its exchange rate fixed one-to-one to the respective national currency. Local currencies are issued in exchange of national currency and thus, unlike transactions in LETS, do not create additional local liquidity (Ryan-Collins 2011, 64). In contrast to many LETS, local currency schemes usually issue paper notes. The issued note usually expresses its local origin by using local landmarks and identifying features in its design.

Local currency schemes mainly aim at strengthening and vitalising the regional economy by promoting the trade of locally produced goods and services. The underlying logic is that regional SMEs, unlike national or international enterprises, usually re-invest their revenue locally and make their purchases locally. The fact that local businesses keep (spend and invest) in the local economy has been expressed as a local multiplier effect (Sacks 2002). The multiplying factor of regional SMEs’ spending for the local economy is considerably higher compared to (inter-)national enterprises, because the money spent keeps inducing economic activity in the region. Accordingly, local currency schemes highlight this local multiplier and their economic goals. In Brixton, for example, the scheme describes itself : “The Brixton Pound (B£) is money that sticks to Brixton. It’s designed to support Brixton businesses and encourage local trade and production.” (Brixton Pound Organisation, no year) Similarly, the Stroud Pound co-operative aims “[t]o stimulate the local economy” (Stroud Pound Co-op 2009).

Local businesses are the most important participating group in a local currency scheme from two perspectives. First, they are thought to be one of the main groups of recipients that benefit from local currencies. The promotion of local independent businesses is a prime aim of local currency initiatives. Accordingly, it is assumed that local enterprises are inclined to accept local currencies out of business-related calculation (Thiel 2011, 118f.). Businesses might hope to promote their own economic goals through participating in a local currency scheme which aims to strengthen the local economy and establish a consumer preference for locally produced goods and services. Secondly, a local currency scheme itself strongly relies on the participation of local businesses. A circulation of local currency is only feasible if local enterprises in sufficient number accept this form of currency. Their participation in high numbers is crucial for the success of a scheme. In order to assess the classification of local currencies as economic projects based on market exchange, I now turn to usage by traders and businesses.

All three cases selected for this study, i.e. the Brixton Pound, the Stroud Pound, and the Vorarlbergstaler, belong to the type of complementary currencies that Blanc labels “economic projects” (see above). They share particular design features, most significantly the fact that they are backed by legal tender. One can easily change Sterling or Euro into B£, Stroud £, or Vorarlbergstaler. Goods and services traded are denominated in legal tender and can be obtained with legal tender, local currency, or a combination. This particular design, the inclusion of businesses, and the initial objective to strengthen local economies constitute common features of local currencies as understood in this paper. Brixton Pound and Stroud Pound were both launched in 2009, being among the first Transition currencies in the UK (Ryan-Collins 2011). Their respective development differs tremendously, however. In Stroud, some 40 businesses participated in 2010, and 10,000 Stroud Pound were issued. Yet the Stroud Pound has not been in use since 2012 when circulation stopped entirely after a long period of insufficient turnover. By contrast, Brixton Pound not only keeps circulating ; in addition to paper notes worth B£ 35,000, the organisation introduced an e-currency scheme in 2011. This makes it possible to pay-by-text using a mobile phone, without any notes changing hands. Around 250 businesses accept B£ notes, and 160 businesses registered for the e-currency scheme (numbers from 2013). The Vorarlbergstaler was launched in 2013, particularly in order to supplement a successful LETS – the Talente Tauschkreis – that was established in 1996. Today, more than 200 businesses in the Vorarlberg region accept the paper notes ; 100,000 Vorarlbergstaler (equivalent to 100,000 Euros) are in circulation. Cashless payment via bank transfer is available for participating businesses. In Vorarlberg as well as in Brixton and in Stroud (when the Stroud Pound still circulated), the turnover in local currency is quite low, compared to overall turnover of the participating businesses. [5]

In the remaining part of this paper, I discuss actual usage of local currencies by businesses and traders. Rather than capturing all forms of usage, I focus on a particular way of using local currencies for so-called social purposes. Based on selected findings from field research in three local currency schemes (Brixton Pound, Stroud Pound, and Vorarlbergstaler), I show that local currencies should not too easily be labelled “economic projects” that are guided by “market exchange”. I do so by focusing on businesses that participate in the schemes (i.e. that accept local currency), and in particular by asking how traders and businesses use local currencies, and if/how they ascribe particular meaning to it. This resembles Zelizer’s approach and its focus on money uses and their meanings. In what follows I offer a brief look at the specific purposes businesses and traders actually use local currencies for. First, I highlight difficulties and hindrances that prevent businesses from using local currencies like ordinary money within a local economic circle. Then, I explore how and for what purposes traders and businesses actually use local currencies. In a way, these two issues are related : earmarking local currencies as particular, special-purpose money goes hand in hand with its limitation as all-purpose money on the local market.

The usage of local currencies by local businesses and consumers differs considerably. Consumers usually use the money for private consumption and keep it only in amounts that they plan to spend. It is up to them how much national currency they convert into local currency in order to spend it at local businesses. Enterprises, on the other hand, cannot decide the amount of local currency they are willing to keep, since this heavily depends on their customers’ usage of local currencies in their shop. The intake of local currency is not only unpredictable, the spending for business purposes is limited as well and depends on the supplier’s acceptance of local currency. Their predicament lies in the fact that most operating expenses are with suppliers outside the local business community.

Overall, the level of transactions conducted in local currency is rather low. This puts constraints on its use and influences the purposes it is used for. Businesses report that sales in Regiogeld often encompass only a handful of transactions in any given week or even month. As by design the currency circulates only within the regional economy, constraints exist on its utility for meeting business expenditure in particular. Enterprises often source products or raw materials from suppliers outside the region who cannot accept Regiogeld. But even within areas where local currencies are valid, opportunities for using them are limited, since only a selection of businesses accept Regiogeld (cf. North 2014). Also, businesses are careful not to burden business partners by making large payments in local currency. The limited capacity of Regiogeld to function as a general medium of indirect exchange within the local economy stigmatises the currency to some extent ; entrepreneurs would “feel bad” (interviewee in Stroud) about using overly large amounts of Regiogeld in payments to other businesses.

Businesses tend to use local currencies not as ordinary money that is just valid only within a limited monetary space. Instead, most businesses perceive Regiogeld as a particular type of money that is significantly less fungible and far less sought after than conventional money. Regiogeld can, in principle, be exchanged for legal tender (sometimes at a fee), but doing so runs contrary to the ideals upon which it rests.

While the theoretical underpinnings of Regiogeld include its conception as a currency that ought to circulate quickly, it is usual, in practice, for businesses to hoard Regiogeld until they have amassed a large enough amount to cover certain specific items of expenditure. They ascribe a particular meaning to it and use it for special purposes. Some use it for their personal spending in participating businesses such as cafés and restaurants, or for purchases like antiques, small valuable items or clothing. To do so, they take an amount of local currency out of the cash box and substitute it with legal tender. From the perspective of the business, local currency is just converted into ordinary cash without any costs. At the same time, local currency still circulates.

Local currencies might also be used for regular business expenditure, albeit with limited spending opportunities in the market place. In some instances, however, businesses can use it for payment of local taxes and fees. Businesses in Brixton and in the village of Langenegg in Vorarlberg, Austria, for example, can pay rates to their local council in local currencies. With regard to Polanyi, this spending behaviour can be regarded as means of payment for “redistributive” purposes. Local currency is in a sense redistributed into circulation : In Brixton, the council offers its employees to being paid their salaries partly in Brixton Pound. In Langenegg, a part of the municipality’s spending is denominated in Langenegger Talente as well. In particular, payments to associations and sports clubs, for example, are done with local currency. One way to use local currency thus is to spend it on taxes and fees.

It is more common, however, for local currencies to be used for other, social purposes, for it to be spent on something “special”. People report typically spending Regiogeld on “something nice” (café owner in Brixton) or “something special” (trader in Vorarlberg). This refers to spending for reciprocity-based purposes. Not only consumers but even business owners who participate in complementary currency schemes tend to earmark Regiogeld for particular purposes rather than seeing it as a type of money which is “normal” in every respect except for its geographically limited validity. Regiogeld thus is often not just money that cannot be used universally, but money that generates its meaning from its own specific purposes. In particular, local currencies are often used in ways and manners that relate to the idea of local currency as an expression of a local community.

Some businesses use local currencies as a present or bonus payments for their staff. Local currency as a present or bonus payment is more conditional than common currency in the sense that the freedom to spend it on products or services of choice remains locally restricted. Such gifts therefore comprise an indirect request to consume locally or regionally. In other words, they are earmarked. Nevertheless, it is still a strong request rather than a compulsion, since local currency can still be converted into commonly accepted currency.

There are further ways of spending that highlight the underlying notion of a “better money” (Thiel 2011) that stands for the sense of community. Such special business expenses are characterised by their convivial nature and might include presents or dining invitations for staff members. I was told, for example, that a local bookseller uses local currency proceeds to purchase cake for his staff from the café opposite. Shared meals and smallscale parties were mentioned in a striking number of interviews. In Brixton, for example, the owner of a restaurant invites his staff to eat out together : “And then occasionally I take the staff for a burger as a kind of treat umm but yeah it’s quite hard, it’s quite hard to spend that volume of money“ (chef in Brixton). This quote shows that earmarking for convivial purposes goes hand in hand with hindrances to spend it for regular business expenditure.

The owners of a pub in Stroud invited friends and staff for a joint meal at a café that accepted local currency. In return, staff from the café visited the pub and paid the bill with Stroud Pounds. As the pub owner explains : “And when it reached 100 pounds maybe after a month, we would go down to a local café that we knew took the Stroud Pounds and we’d take people for lunch or staff for lunch. … like we’ve got a couple let’s all go out for lunch´, you know. So we’d go for lunch. And then the same night that café would bring their staff up here andtequila for all´ and give me the money back. You know, it was just a bit of fun” (pub owner in Stroud).

Such usages form a paradigmatic example for the use of local currencies for covering “special” expenses and for practices which constitute it. Commensality, i.e. sharing a meal together with a group, is one of the activities that creates community bonds and forms the basis of our sociality (Hirschman 1996). Shared meals are expressions of sociability and generalised reciprocity. Communities emerge from and express themselves in social occasions like this.

The communality of this usage is taking place on two levels. Firstly within the local business, as staff members are invited. Secondly, between local businesses since the usage of local money is reciprocal between the two groups. These uses of local currencies for social, or convivial purposes should not be seen simply as the product of individual decisions. They are, rather, the product of interactions between the transacting parties. Advance discussion takes place between potential transaction partners about how local currencies could be used and also about the extent to which it ought to be used in ways that represent their special meaning. Participating traders develop an appreciation of local currency as a special means of payment through this dialogue and solidify this attribution of significance through their collective practices. Due to the restrictions of the local currency, there is need to find out if (and to what ceiling) notes are accepted or not before a purchase is made. The monetary transaction can only be effected if the traders have no problem in accepting and re-using the notes. These practices refer to Zelizer’s concept of relational work (Zelizer 2012, 149).

As such, Regiogeld is a kind of money which defies the depersonalisation and reification of social relations to some degree. It does not serve as a reified, instrumentally rational means on the market, but, to a considerable extent, as a value-oriented rational (wertrationales) means for community purposes. Participants describe the use of Regiogeld as a more personal form of payment, especially as it often serves as a conversation starter. In concrete terms, the community spirit may be felt in such little things as a chat during the payment process or a brief exchange of views on the local currency scheme or the notes.

This special characteristic can be seen as the flip side of low turnover. Sales in Regiogeld are not high enough to provide a significant boost to the circulation of money in the regional economy. From the business perspective of a single enterprise, a high turnover in Regiogeld could also create difficulties, since the local currency would then need to be used like a conventional currency and outlets for such uses are lacking. Low turnover, however, eases the attribution of meaning described here and the use of Regiogeld in ways which are special and different.

Findings from the Brixton Pound, the Stroud Pound, and the Vorarlbergstaler show that local currencies (Transition currencies, or Regiogeld) are used by traders and businesses in a particular way that is different from their use of ordinary money. In other words, traders tend to ascribe a particular meaning to Regiogeld. This meaning differs from that of conventional money in the sense that local currency is regarded as a more social currency. It is (or, regarding to many participants : should be) predominantly used for convivial, community-related purposes. The characterisation and classification as an “economic project” (Blanc 2011) confuses the original objectives of the schemes and their design principles with the actual usage of local currencies.

A comparison between the actual usage and the meaning ascribed to local currency with the original objectives of the scheme reveals further insights : local currency is (at least partly) intended to serve as a localised medium of exchange that strengthens local businesses and the local economy. The rationale is that the circulation of local currency with its high velocity increases demand for local products and services since it cannot be used outside the local economy. An implication is that local currency is used on the local marketplace and is in fact perceived as a means to support local businesses. Actual practices show, however, that the participants of local currencies usually do not regard them as a convenient means of indirect exchange but as a specific monetary form with its own meaning. The difference between usage patterns and intentions can be linked to the two forms of earmarking identified by Zelizer : (1) a new form of currency is created (with given objectives), and (2) it is earmarked by users (for particular purposes). In particular, businesses tend to use local currencies for special purposes that for example include bonus payments or Christmas presents for staff members. Moreover, business owners and managers also invite staff members to group nights out with meals or drinks. This shows how local currencies might contribute to community building. The specific purposes for which the money is used also point towards the significance of reciprocity and the gift in complementary currency systems. Participating businesses utilise Regiogeld for particular purposes which largely express and nurture the social and sociable character of Regiogeld. As such, Regiogeld functions more as a medium of payment within a specific cycle of gift exchange and less, as it is often conceived of, as a general (albeit geographically limited) medium of exchange in the marketplace. To put it straight : commensality counters commerciality.

The other side of this story is that economic performance (in terms of turnover and circulation) is limited. Total turnover in local currencies is rather low, and participating enterprises often cannot use local currencies entirely for their conventional business purchases. Actual money uses and the special meaning that is ascribed to local currencies resemble and in a sense compensate for these shortcomings. All in all, local currency schemes exist in a state of unresolved tension. Their aims include the stimulation of local spending in order to give a boost to local businesses, but most local currencies do not meet such economic expectations placed on them. Evaluating Regiogeld projects purely in terms of their turnover and their (in)ability to support and strengthen spending in the regional economy would, however, be somewhat short-sighted. It would ignore their essence as money earmarked for community-purposes in ways that are distinguishable from the uses of conventional currency.

Bernard, H.R. (2006) Research methods in anthropology : qualitative and quantitative approaches, Lanham, MD : AltaMira Press.

Blanc, J. (2011) Community, Complementary and Local Currencies` Types and Generations. In : International Journal of Community Currency Research 15 (D) : 4–10.

Blanc, J. ; Fare, M. (2013) Understanding the Role of Governments and Administrations in the Implementation of Community and Complementary Currencies. In : Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics 84 (1) : 63–81.

Brixton Pound Organisation (no year) Why use Brixon Pound ? http://brixtonpound.org/why-use-b-2/b-benefits/ (22/10/2015).

Degens, P. (2018) Geld als Gabe. Zur sozialen Bedeutung lokaler Geldformen. Bielefeld : transcript.

Degens, P. (2013) Alternative Geldkonzepte – ein Literaturbericht. MPIfG Discussion Paper 13/1. Köln : Max-Planck-Institute for the Study of Societies.

Dodd, N. (2014) The Social Life of Money, Princeton, New Jersey : Princeton University Press.

Hallsmith, G. ; Lietaer, B.A. (2011) Creating Wealth : Growing Local Economies with Local Currencies, Gabriola Island, BC : New Society Publishers.

Hirschman, A.O. (1996) Melding the public and private spheres : Taking commmensality seriously. In : Critical Review 10 (4) : 533–550.

Lainer-Vos, D. (2013) The Practical Organization of Moral Transactions : Gift Giving, Market Exchange, Credit, and the Making of Diaspora Bonds. In : Sociological Theory 31 (2) : 145–167.

Mauss, M. (1990) The Gift : the Form and Reason for Exchange in Archaic Societies. London/New York : routledge.

Melitz, J. (1970) The Polanyi School of Anthropology on Money : An Economist’s View. In : American Anthropologist 72 (5) : 1020–1040.

Michel, A. ; Hudon, M. (2015) Community currencies and sustainable development : A systematic review. In : Ecological Economics 116 : 160–171.

Mikl-Horke, G. (2011) Historische Soziologie, Sozioökonomie, Wirtschaftssoziologie, Wiesbaden : VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

North, P. (2014) Ten Square Miles Surrounded By Reality ? Materialising Alternative Economies Using Local Currencies. Antipode 46 (1) : 246–265.

Osteen, M. (2002) Introduction : questions of the gift. In : Osteen, M. (ed.) The Question of the Gift. Essays across disciplines. Routledge Studies in Anthropology. London ; New York : Routledge : 1–41.

Peacock, M.S. (2014) Complementary currencies : History, theory, prospects. In : Local Economy 29 (6–7) : 708–722.

Peoples, J.G. ; Bailey, G.A. (2000) Humanity : an introduction to cultural anthropology, Belmont, Calif : West/Wadsworth.

Polanyi, K. (2001) The Great Transformation. The Political and Economic Origins of our Time 2nd Beacon Paperback ed., Boston, MA : Beacon Press.

Polanyi, K. (1968) The Semantics of Money-Uses. In Primitive, Archaic and Modern Economies. Essays of Karl Polanyi. Garden City, New York : Anchor Books : 175–203.

Polanyi, K. (1957) The Economy as Instituted Process. In : Arensberg, C. M. ; Polanyi, K. ; Pearson, H.W. (eds.) Trade and Market in the Early Empires. Economies in History and Theory. New York ; London : Free Press, Collier-Macmillan : 243–270.

Naqvi, M. ; Southgate, J. (2013) Banknotes, Local Currencies and Central Bank Objectives. In : Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin 53 (4) : 317-325.

Ryan-Collins, J. (2011) Building Local Resilience : The Emergence of the UK Transition Currencies. In : International Journal of Community Currency Research 15 (D) : 61-67.

Sacks, Justin (2002) The Money Trail. Measuring your Impact on the Local Economy. London : New Economics Foundation.

Seyfang, G. ; Longhurst, N. (2013) Growing green money ? Mapping community currencies for sustainable development. In : Ecological Economics 86 : 65–77.

Simmel, G. (1995) Die Großstädte und das Geistesleben. In : Kramme, R. ; Rammstedt, A ; Rammstedt, O. (eds.) Georg Simmel, Aufsätze und Abhandlungen 1901-1908. Bd. 1. Gesamtausgabe Bd.7. Frankfurt a. M. : Suhrkamp : 116-131.

Simmel, G. (1989) Philosophie des Geldes, Frankfurt am Main : Suhrkamp.

Steiner, P. (2009) Who is right about the modern economy : Polanyi, Zelizer, or both ? In : Theory and Society 38 (1) : 97–110.

Stroud Pound Co-op (2009) Memorandum of Association. Stroud.

Thiel, C. (2012) ‘Moral Money – The Action Guiding Impact of Complementary Currencies : A Case Study at the Chiemgauer Regional money’. In : International Journal of Community Currency Research 16 (D) : 91-96 .

Thiel, C. (2011) Das ‘bessere’ Geld. Eine ethnographische Studie über Regionalwährungen, Wiesbaden : VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Zelizer, V.A. (2012) How I Became a Relational Economic Sociologist and What Does That Mean ? In : Politics & Society 40 (2) : 145–174.

Zelizer, V.A. (2011) Economic Lives : How Culture Shapes the Economy, Princeton, NJ : Princeton Univ. Press.

Zelizer, V.A. (1994) The social meaning of money, New York : Basic Books.

[1] For a detailed account of my PhD research project, see Degens (2018). I carried out field work and conducted interviews with participating traders and businesses in Brixton (7), Stroud (4), and Vorarlberg (6) as part of a research project on local currencies. Stroud is a specific case as circulation of the Stroud Pound stopped end of 2012 ; interviews were done retrospectively. The Brixton Pound and the Vorarlbergstaler are considerably more successful, their circulation slightly increases. Interviewees were selected purposively in the field (Bernard 2006, 189 – 191), and I aimed at including a broad variety of cases. Especially, it was ensured that the samples include cases with diverse characteristics regarding fundamental criteria (duration of membership, intensity of membership, local currency turnover and industry as well as satisfaction with the local currency scheme). Open and semi-structured interviews with participating traders and businesses lasted between 25 and 80 minutes and took place in 2014. Interviews were recorded, transcribed and coded.

[2] It is not clear that Polanyi believes that modern money actually does resemble the fungible and homogeneous idea of a pure market money. In the Great Transformation (2001), Polanyi argues that attempts to make money a commodity in this sense failed. The debate about Polanyi and his apparent tendency to sharply separate premodern and modern economies (and monetary systems) is not object of this paper. An early critique of the notion of all-purpose money offers Melitz (1970).

[3] There is, however, disagreement regarding the categories gift and money. In anthropology, some refer to the gift as absolutely moneyless exchange (e.g. Peoples/Bailey 2000, 108). In my view, there is no need to categorically restrict gift and reciprocity to non-monetary forms of exchange. Zelizer and others have shown that money is not always used as a commodity on the market, and in fact might be given as a gift. Lainer-Vos (2013) for instance uses the case of diaspora bonds to show how monetary investments might both comprise gift giving and market exchange elements.

[4] Zelizer shifts her focus from the notion of earmarking towards circuits of commerce and relational work in order to better grasp the relationality of practices that constitute economic relations (Zelizer 2012).

[5] In a sense, both Brixton Pound and Vorarlbergstaler should not be reduced to a mere local currency scheme because their activities and scope go well beyond the circulation of alternative money (for a full description, see Degens 2016). The Brixton Pound organization, for example, has broadened its scope since its launch in 2009. Nowadays, the organisation describes itself as “a local currency, community lottery, grassroots funder and now a pay-what-you-feel café” (see http://brixtonpound.org/ (28/10/2016). For a self-description of the Vorarlbergstaler see http://www.allmenda.com/content/vtaler (28/10/2016), for the Talente Tauschkreis http://www.talente.cc/ (28/10/2016).